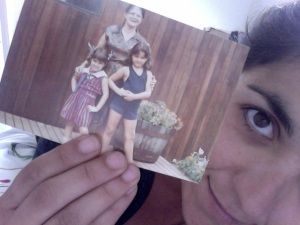

the ways we raise children

my muchacha -directly translated as “woman,” it is the latino word for nanny/housekeeper- was named paquita (pa-kee-ta). i can’t recall her real name, or it was never told to me; i don’t know if that’s how you spell her nickname, but that’s how i always saw it. she was in her 50s or 60s with leathery brown skin and large rimmed glasses, and her hair was always pulled back with barrettes in a long braid that reached the small of her back. i would hide in her skirts and she filled my belly with pupusas and fried eggs cut to look like suns. my sister’s muchacha’s name was cuca (coo-cah), and she taught me how to swim through treachery in the shallow end. we loved them, and fully believed they loved us.

a young girl in her early teens used to live in my grandparents’ house in colombia. she would wear a white uniform and seeing her in civilian clothes was like seeing someone without their glasses. she played with us like a cousin not a muchacha, or so i thought, until an adult would yell her name, “maria claudia!” and she would run off at their beckoning.

my grandfather, papahugo, took maria claudia in at a young age; offering to pay for her education and lodging while she provided my young aunt companionship and helped around the house. he also asked her family to live in his one story office building to act as security in his absence. maria claudia never ate friday siesta lunch with us in the dining room. instead, she would come in and out through the kitchen, helping my grandma serve.

before my grandpa died, my grandparents took on another ward, as it were, making the same agreement with her family. neyla is now in her early twenties, and she started living with my grandparents when she was about fifteen. she doesn’t wear a white uniform, but she might as well. when my grandma, mamaia, got cancer a year or so ago, neyla dropped out of school to take care of her. she slept in mamaia’s bed every night and spent all day with her watching television or playing on her blackberry. she would take her to chemo, cooked her meals, did laundry, and helped her serve friday siesta lunch. when i was staying with them in colombia, neyla would tell me how she mourned papahugo. how he used to take her out for drives in his car and how she loves him like a father and misses him, but in the middle of the story, mamaia or my aunt or my uncle or my five year old cousin would yell, “neyla!” and off she’d go.

it’s a twisted tradition: offering to take the child of some poor family; to educate, feed, and raise them. this seeming act of benevolence stinks of cheap labor, indentured servitude, and psychological abuse. they treat them like family as long as it suits them, and then demand they serve in ways that none of my cousins nor i would have ever been expected. neyla sees herself as family, and was led to believe this by my grandparents, but no one else in the family identifies her as such. all i could think while i was there was, “what’s going to happen to her when mamaia dies?” will anyone offer to finish paying for her school, give her my grandma’s room to live in, or support her transition to an independent life? doubtful.

for safety reasons and the performance of heavy lifting, my grandparents always had a man working in the house as well. recently, they had a young man named wilmer, but my grandma called him wilber from day one. neither he nor anyone else ever corrected her. he was also in his early 20s, started working in the house when he was 15, attended a technical school, and had a young girlfriend who was very sick. i gained his confidence while i stayed with them, and before i left barranquilla, he and i commiserated on what a horribly tense and dysfunctional household it was -there was a lot of matriarch battling between my grandma and aunt- and how unnerving his role of errand boy was. he told me they paid him shit and treated him poorly, and yet he felt some loyalty to my grandma, especially since she got cancer. i tried my best to lead by example in that house, particularly with my little cousin; i would clean my own things and serve myself, but it only functioned as proof of my otherness to them. wilmer and i would exchange winks and knowing smirks during siesta lunch. he also told me how neyla would treat him worse than the rest. claro, i thought.

by the time i left colombia, wilmer had left. he was having personal difficulties and my family felt he just wasn’t performing up to par. they lamented the unfortunate circumstances of his dismissal, particularly his apparent disregard for all they gave him; for welcoming him into the family; for letting him eat lunch in the laundry room off the kitchen; for offering him advice and then gossiping about him when he wasn’t there. two months after i returned to the states, mamaia passed away. i have no idea what has become of neyla or wilmer, and, like paquita, cucona, and maria claudia before them, no one seems to know, or care.

Powerful essay.